A Still Room in Brooklyn

I grew up in a quiet apartment in Brooklyn, where the noise outside softened by the time it reached us, and the inside was its own contained world of low hums and slow light.

Outside: distant traffic, the occasional siren, neighbors arguing just out of sight.

Inside: the quiet churn of the fridge, the fan’s steady spin, the screen’s gentle whir. Beneath it all, the building seemed to hum—pipes, wires, something electric moving through the walls like breath.

I stayed inside. My mother was protective, sure, but I didn’t need much convincing. I wasn’t drawn to the street the way some kids were. The world that mattered to me was quieter, contained, screen-lit. It’s where I turned into a person—like I wrote about once.

My portal was the computer.

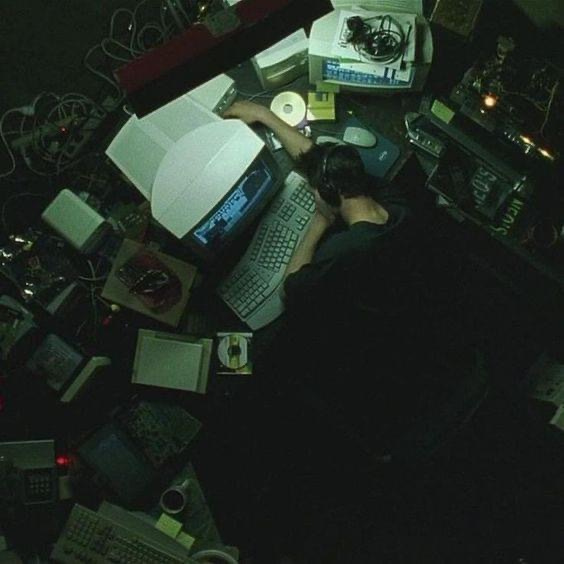

I used to pull up that first scene of Neo from The Matrix (1999) on YouTube just to hear “Dissolved Girl” by Massive Attack. That track, that tone, that stillness—it all felt adjacent to something I had been experiencing long before I had a name for it. What struck me wasn’t the plot, but the atmosphere: the silence, the screen glow, the stillness of someone wired into something. That late-’90s cyber-aesthetic felt adjacent to my own kind of digital world, something I had been building without the language for it.

It sat on a narrow desk in my bedroom, centered against the right-hand wall—the first thing you’d see when you stepped inside. The monitor buzzed faintly. The speakers made everything sound warmer than it probably was. I never actually fell asleep there, but the idea of it wouldn’t have been strange. It felt like a place someone could fall asleep. It felt like home.

My Dell Dimension PC came with a built-in audio visualizer. Windows Media Player. Blue waves, floating lines, geometric loops that moved in sync with whatever track was playing. It held my attention. I wasn’t watching music videos. I wasn’t multitasking. I was just…watching sound. Watching it bend, shimmer, stretch, pulse. Sitting still at the desk, letting the audio and the visuals fold into each other. That was the experience.

Like Neo, maybe sitting still at the desk was the first step toward becoming. I wasn’t looking for the Matrix, exactly, but I was looking for something. Some signal. Some shimmer. Some quiet sense that the screen could open up and lead somewhere else.

Here’s a simple question I keep circling back to:

What is the point of an audio visualizer?

Not just technically, but emotionally. Why do we sit there and watch sound move? Why do we let it take over the screen?

For me, it’s been three things:

A distractor — from anxiety, from overstimulation, from myself.

A focus anchor — for deep work, coding, writing, thinking.

A thing to focus on — not for function, but for mesmerization. A moving stillness.

In some strange way, audio visualizers have become the background radiation of (my) modern solitude. They’re not meant to entertain so much as envelop. They fill the room without demanding attention. They say, “I’m here with you, even if no one else is.”

That’s part of what I’m trying to build with Black Speech TV—a space that hums back. Something slow. Something ambient. Something archival. Something you can sit with. Something that sits with you.

Black Noise and Layered Listening

“Black noise” is sometimes defined as silence, or the absence of energy across all frequencies. But I hear something else in it.

I hear the hum of the Black interior. The hum between the sermon and the scream. I mean the background sound of a people who have had to listen their way into survival.

In this project, Black Speech TV, I’m layering Black noise beneath Black speech. I’m asking what happens when the ambient meets the archive. What does it mean to listen to Malcolm X while a barely-there drone washes underneath? What emerges when a Toni Morrison passage collides with room tone, synth mist, or the flutter of digital wind?

I’m reminded of that moment in Invisible Man (1952) when the narrator listens to Louis Armstrong. He says:

“I not only entered the music but descended. I heard not only in time, but in space as well.”

That descent is key. Most media pushes us to rise, to climax, to conclude. But what if this project invites a different kind of movement—not upward, but inward? What if listening is a way of falling back into ourselves?

Pregeneric Myths and Rituals of Descent

Robert Stepto, in From Behind the Veil (1979), writes that African American literature is shaped by what he calls “pregeneric myths.” These are recurring narrative patterns that often structure the work before it settles into any formal genre. One such pattern is the ritual of ascent—a narrative arc that begins in bondage, passes through literacy, and ends in the pursuit or attainment of freedom.

This project might be doing something similar…yet distinct.

There’s no final freedom here. No redemptive arc. No grand climax. Instead, there’s a ritual of descent: into audio, into noise, into history, into stillness. You sit with it. You hear it. Maybe you catch something. Maybe you don’t.

But something’s happening. Or nothing. Or it’s just looping, like a vinyl left spinning at the end of Side B.

I trust that something will happen… or not… or something later…

Black Speech TV: The Interface

The experience is simple. It’s a site where you can:

Surf between different “channels” of Black speech—just speeches and poems for now, but eventually sermons, novel readings, and more.

Each is paired with ambient sound or what I’ve found is called “Black noise.”

Eventually, I want to display the audio’s waveform in real time—so you’re not just hearing the Black speech form, but watching it take shape.

Part archive, part audio lounge, part sonic ritual. No playlist. No comments. Just space.

First Sounds

I think about how Black speech began on the slave ship—people from different tribes, different languages, trying to communicate in the dark. It wasn’t a shared tongue at first. It was moans, cries, broken syllables, gestures. Sound as survival. Meaning made under duress.

That moment—fragile, brutal, creative—was an origin point, where language began to blur, overlap, and become something else.

This project tries to listen for that early current—and to let these Black speech forms flow into one another, like signals still trying to find each other across time.

Why I Built This

Because I grew up listening to the internet.

Because Black sound deserves slow interfaces.

Because I wanted to make something that didn’t ask for attention, but allowed for it.

Because someone out there is still listening.

Because I was buffering too.

Because I was mesmerized by movement.

And because I wanted to ask a simple question:

What happens when the ambient meets the archive?

This version of Black Speech TV is just the beginning. It’s a space for passive inspiration, for lingering, looping, drifting. But future iterations may carry more structure: fact cards, historical context, archival links. I imagine a screen where slow speech lives alongside slow metadata. Where you can listen, but also learn gently, ambiently.

Because Black knowledge can be loud. But it can also hum.

Acknowledgments

Grateful to the Price Lab for Digital Humanities at the University of Pennsylvania for organizing Dream Lab 2025, and to everyone who participated in the Black Speculative Digital Arts and Humanities course. Thank you for giving me space to think, drift, and begin building this project out loud.