I don’t remember the first time I went online. But I remember how it felt. Not profound. Not life-changing. Just…fun. Like a new kind of toy.

And yet—somewhere in that fun was a flicker of something else. Something I wouldn’t have had the language for at the time. The internet would become many things to me over the years: escape, mirror, engine, hiding place. But in those early days, it was just a screen that lit up when I asked it to.

After Dark, But During School

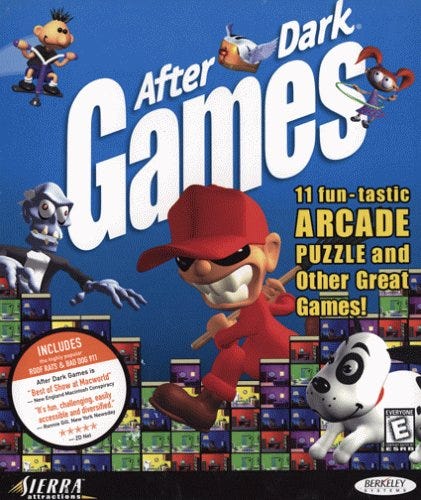

In elementary school, we had “computer class.” It sounds fancier than it was. Mostly, it meant sitting in front of candy-colored iMac G3s (I think…maybe?) and playing whatever was installed. I remember one game — After Dark Games (Still a wild title for something for use in a school) — and especially a lawn mowing mini-game I weirdly loved.

I wasn’t learning to code. I wasn’t thinking about the future. I was just a kid clicking through pixels. But still—something stuck. Something settled into me. Those machines weren’t just fun. They were flexible…They responded. They opened. They did things. And without knowing it, I started to think differently about possibility—but not in the grand sense. Just...the kind you feel when something responds.

Some Model Called Dimension (?)

The real shift came when my mom bought me my first computer. I think I asked for it, though I don’t remember how. What I do remember is this: she used to take me to the library, and I’d head over to the public computers to play games on cartoonnetwork.com.

Those games weren’t nothing. Some of them were actually really well made—surprisingly polished, considering they were free and browser-based. The Teen Titans brawler stands out the most. It’s still somewhere in my memory: all pixel edges, smooth Flash movement, and just enough challenge to keep me clicking. I wouldn’t call them a treasure, but I definitely sank hours into them. And looking back, I think that quiet, repeated desire to play—to be near those games—was probably the beginning of something. Not just liking computers. Wanting to be around them.

So we got a Dell. A beige tower—maybe a Dimension model, though I wouldn’t have known the name at the time. I don’t remember the specs, and I probably didn’t care. What I do remember is that it worked. It sat under the desk, it turned on when I needed it to, and it gave me access to the things I wanted to do. For a long time, that machine became a quiet constant in my life. Not because it was impressive—just because it was there. And because it was mine.

The First One That Wasn’t Me — But Was

Middle school brought RuneScape. Not as a passing hobby, but as a space—a weird, pixelated world where I could fish for XP and crack jokes with people I’d never met in person. I’d be up late, running quests or hanging out in banks, half-talking, half-playing, always plugged into something I didn’t fully understand but wanted more of.

This was still the dial-up era—back when using the internet meant no one else in the house could use the phone. That detail feels ancient now, but back then it shaped everything. Time online was a resource. It had to be claimed, defended, rationed.

And during those sessions, I stumbled into forums. Not just for the games—but for the identities. I created a username: VenomArcade. It sounded cool to me at the time. Sharp. Mysterious. A little performative. But that was the point. Forums were where I learned how to be someone—or at least, how to try on someone.

The site I joined was popular but messy. It had game walkthroughs, chat threads, strange corners, and a whole lot of content no preteen should’ve been reading. But the internet didn’t come with bumpers. You didn’t know what you’d run into until you were already there. Sometimes you were just curious. Sometimes you were trolling. Sometimes you were lonely and didn’t have the words for it yet.

Looking back, I don’t think I knew what I was becoming. But I was becoming something. Or someone. I was still just playing games. But something was shifting. Computers weren’t just machines I used—they were places I went. And even if I didn’t know what I was looking for, I was starting to pay attention.

Downloads and Disconnections

By high school, I was using Limewire to download music—hip hop, mostly. It didn’t feel like a decision at the time. I just started typing in song names, following the artists who caught my attention. Sometimes the files were mislabeled. Sometimes they came with viruses. The computer would freeze, or the speakers would stop working. I’d mess around with the settings and feel like I was fixing something. Like I was doing something clever. I wasn’t. But I was trying.

And in the background of all that—between the downloads and the crashes—I was falling in love with rap music. The rhythms, the wordplay, the energy of it. It opened something in me. Gave language to things I didn’t know I needed words for. It’s still with me, in ways I don’t always name, but always feel. And when I write, I think I’m trying to reach for the rhythm, the wisdom, and the weight those songs carried

Around the same time, AIM was how we talked. Status messages, away messages, inside jokes—you could say a lot without saying much. It made friendships feel bigger, more performative, more public. But it also made them more fragile.

I don’t remember exactly what I posted. Something vague. Maybe dramatic. But whatever it was, it changed things. A few people stopped talking to me after that. And the silence that followed stuck around longer than I expected it to.

Looking back, it wasn’t just that I made a mistake. It was that I didn’t know how to come back from it. I didn’t have the tools to repair what I’d broken—or maybe what I thought I’d broken. And even now, there’s a part of me that still holds that moment. Not like a wound. More like... a shape.

Sephiroth, MySpace, and the Shape of the Web

By the time MySpace came around, the internet wasn’t mysterious anymore—but it was still wide open. It felt like there was room for everything: fan sites, forums, pixelated banners, blogs with blinking cursors and broken image links. Nothing was polished, but everything was alive.

I had a MySpace page, like most people. I remember adding songs to it—whatever felt right that week—and changing my background to a wallpaper of Sephiroth from Final Fantasy VII, even though I hadn’t played the game. I just knew who he was. He felt iconic, mysterious, kind of powerful. It made sense in the logic of teenage identity: you didn’t need to be something to broadcast it.

The internet then was stitched together by people trying things—messy, inconsistent, deeply personal. There were algorithms, sure, but none that we noticed. No feeds. No filters. No one telling you what you should see next. Just vibes, HTML, and a lot of trial and error.

Today’s internet feels like the opposite. It’s seamless. Polished. Platformed. Most people don’t “have a website” anymore—they have accounts. Everything lives under the umbrellas of Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, or Apple. Blogs look the same. Status updates blur together. It’s all been flattened. Optimized. Cleaned up.

We gained convenience. We gained scale.

But we lost that strange, beautiful freedom to make things ugly. To build without knowing what we were building for.

Learning to Become from People Who Weren’t Real

For me, the internet will always be tied to Toonami. I’m not sure why exactly. Maybe because both were screens I returned to—not just for entertainment, but for glimpses of masculinity I could actually sit with—ones that felt gentler, more expansive, more in tune with who I was trying to become. The kind I didn’t always see in my day-to-day life—not out of harm, but out of hardness. Out of people doing their best with what they’d been given.

There’s one bump I always come back to. It was called Broken Promise (Dreams)—just a short interstitial between shows, set to a haunting piece of electronic music. “Face your destiny without fear, but with courage,” the voice said, just before a countdown launched a spaceship into the stars.

I didn’t know why it mattered so much then. I still don’t, not fully. But it did.

I was a Black boy sorting through reflections—some too harsh, some too hollow—trying to find a version of manhood that wouldn’t make me disappear. My stepfather was too hard. I was too sensitive. And Goku? He wasn’t real. But somehow, he made room for me. A quiet kind of room. Not perfect. But enough.

And the internet? It was the other screen. The one I could control. The one where I could piece myself together slowly—one Toonami quote, one Limewire download, one avatar at a time.

Two screens, side by side. One feeding the imagination. The other feeding the self. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was learning how to become—right there, in front of both.

In Front of a Screen Again

The old internet is gone. So is the library hour. So is cartoonnetwork.com.

I don’t know if I was better off because of any of it.

But I was there.

And I did what I could with what I found.

I built things.

I broke things.

I stayed up too late.

I kept logging on.

And now, all these years later, I’m in front of a screen again.

Typing this.

Trying to understand who I became.

Not arriving. Just reflecting. Still turning the pieces over.

Maybe that’s all this ever was.

Not a destination—just another kind of trying.

Sidebar: VenomArcade, Crockford, and the Code Behind the Curtain

Here’s something I think about sometimes:

While I was mashing buttons in that Teen Titans game or crashing my Dell with Limewire downloads, Douglas Crockford was quietly helping to shape the future of the web.

He didn’t invent JSON, but he saw its potential—how it could let browsers and servers speak to each other more cleanly, more simply, without the heaviness of XML. His work helped lay the groundwork for what would become the modern internet: apps, platforms, even games.

Did his code touch cartoonnetwork.com? Probably not. Those Flash games lived in their own little world, built mostly with ActionScript, not JavaScript. But if you zoom out far enough, the tools Crockford helped standardize are the same ones that allowed everything to evolve—toward interaction, toward connection, toward something we’re still making sense of.

So no, VenomArcade and Crockford never crossed paths. But maybe they were both part of the same moment—just on different layers of the stack. One trying to figure out how to be a person. The other quietly rewriting the logic behind the screen.